6. Epiphanies

David Inshaw's painting has always been essentially autobiographical in character, a means of giving form to the subjective experiences of his life. This is very much part of the romantic tradition stretching back into the nineteenth century, in which landscape has been used to express states of mind such as exhilaration, melancholy and joy, that is well understood in this country and Northern Europe in general. Samuel Palmer, Paul Nash and Stanley Spencer, for example, all derived much of their strength and individuality from it. It is no coincidence that, together with Balthus, these are the painters who hold the greatest and most lasting significance for Inshaw. Yet he is a very different kind of artist from any of these, finding his own highly individual solutions through an emotional straight-forwardness that may appear strong meat to a figurative tradition that so often seems close to illustration.

Bonfire and Gate I, 1992

Inshaw's paintings are essentially conduits of feeling; personal dramas that depend on the integrity and self under- standing with which he treats the emotional situations that brought them into being, their strength and directness enabling them to push their way into our minds, forcing us to recognise them as our own.

Bonfire Night, Hay Bluff I, 1992

Since the early 1970s and paintings like The Badminton Game, the appearance and emotional range of Inshaw's art, though not its essential sources of inspiration, have revealed a clear evolution that gives to his later work a complexity and expressive range far beyond anything he has achieved before. One look at his bonfire paintings is enough to make this immediately apparent. Here the Welsh landscape around Hay-on-Wye forms the backdrop for a literally pyrotechnic display of virtuoso painting. The vivid shocks of colour – viridian and emerald green, cadmium yellow and venetian red – are painted with a much greater density and fluidity of brushwork than ever before.

Artist and Wife, 1994

This is by no means to say that the two other principal groups of recent work, the Wiltshire landscapes and the beach paintings, contain work of any less force or intensity, as one look at paintings like Hand Holding [next page] or Artist and Wife make immediately obvious.

.jpg)

West Bay with Helicopter (Sunburnt Shoulders), 1996-98

Though based in Clyro, Wales, from 1989 to 1995, Inshaw has retained a small studio in Devizes, Wiltshire, where he first went to live in the early 1970s, and thus has divided his painting time between the two places. The still point of the turning world and Hand Holding, together with most of the other pure landscapes from this period, are about this particular district of Wiltshire which has, over the years, become invested with a powerful degree of inspirational significance for him. The curious curving bridge with its diamond-shaped sign that acts as a setting for these two particular paintings, is situated on a remote stretch of the Kennet and Avon canal in the Vale of Pewsey, a downland landscape that has always exerted a special hold on the artist's visual imagination. He can rarely have painted it in a more reflective and passionate spirit than in these two works, where the figures of the people he loves appear almost like emanations of the intensely observed landscape.

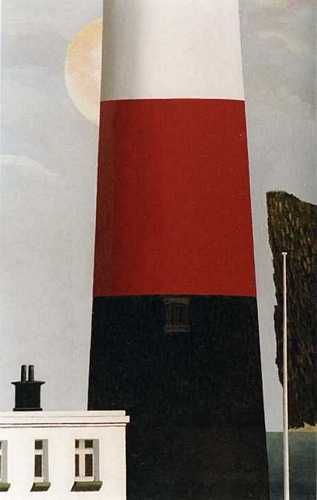

Lighthouse, 1994

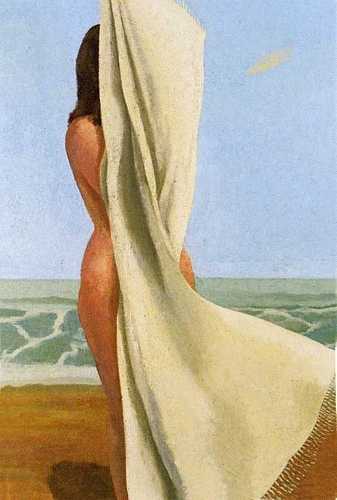

Similar qualities are also to be found in the beach series of paintings, which are loosely based on memories of holidays in Cornwall and Pembrokeshire. The range of moods these paintings contain is particularly varied, ranging from the ironic, almost surrealist ambiguities of the superb Lighthouse to the teasing sexuality of the three Towel paintings with echoes of the early nineteenth-century American painter Raphaelle Peale's After the Bath, to the quizzical bewilderment at the transitoriness of human feelings to be found in Artist and Wife. The sandcastle subjects also arouse both simple and complex sensations, an evocation of the artist's youth providing a quite unmistakable metaphor for the mutability of human understanding.

What is true of all his paintings is the way in which the strength of feeling they contain finds its way so surely into our subconscious. Like a dream, an Inshaw landscape is a landscape we have no option but to enter. They draw us in by the sheer confidence and conviction with which they are painted. Once visually hooked we are then compelled to go much further and deeper, to consider the very particular sense of moment or transience we find there. We do not need to know what particular state of mind led him to arrive at this visual equivalent, only that we recognise, at a very atavistic level, that instant when colour and form, image and emotion, arrive at a point of cohesion.

Sandcastle, 1992

Just as the great American Joseph Cornell's art was nourished by moments of heightened experience and perception of an entirely haphazard kind – 'epiphanies' as he termed them – which could bring 'unexpected and extravagant joy of discovery amid nearby surroundings', so Inshaw finds his own epiphanies in bonfires on the Welsh hills, figures crossing remote bridges in the Vale of Pewsey, or in the scrubby wasteland of thistles and small birds surrounding a derelict brick barn outside Devizes. However extraordinary the points of departure for these paintings might be, we arrive with the artist at a point of resolution and reconciliation that is also exhilarating and celebratory.

Woman, Towel and Wave, 1995-96