8. Moments of vision

In the early 1970s David Inshaw painted The Badminton Game, the first of his mature works to capture the public imagination. It still does today, being the unexpected star of the Art of the Garden exhibition at the Tate Gallery, London, in 2004, very much the public image of the show and used repeatedly to publicize it. With its arrested, frozen movement – like the still from a film in which the actions of the protagonists, the 'before' and 'after', are left entirely to our imaginations and a soundtrack to the scene that is, so to speak, resolutely soundless – we ourselves bring to it the distant sounds of nature and human life, and suddenly we find ourselves drawn into the scene. As with all great paintings, the artist makes his dream, his reconciliation with his imaginative past, our tangible reality also.

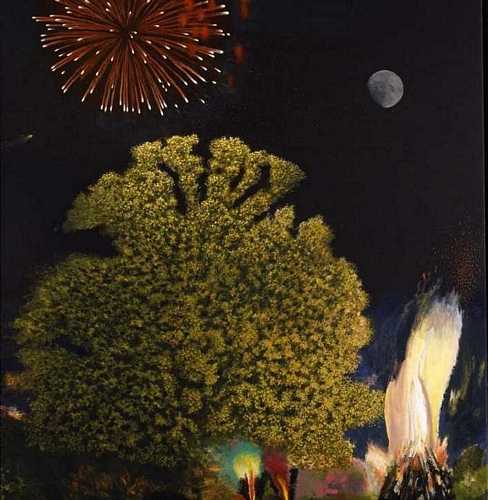

More recently, in Oak Tree, Bonfire and Fireworks, Inshaw has created a work of similarly iconic character, one which may prove, in time, to be an even more

profound and significant achievement still. For in it he abandons the figure altogether and, by allowing the elements of the natural world to stand in their place,

arrives at sensations of timelessness and soundlessness – absent presences if you like – that, taken together with the lesson from Thomas Hardy which has

always underpinned his most characteristic paintings, 'that the beauty of association is far superior to the beauty of the aspect', has embarked on the

creation of a visual language where nature, by itself, can imply an intense and complex range of personal and highly sensual feelings.

It is a painting worth trying to deconstruct a little for, in the process, it says much about the innate poetics of Inshaw's art. The most startling effects are

perhaps in the upper half of the composition, where the exploding corona of the rocket, the very symbol of evanescence and insubstantiality, remains frozen forever at the

apogee of its glory, the infinities of time it suggests compounded by the comet and moon to either side. These sensations are further reinforced by the parallel sequence

of images on the ground below – the massive fan of firelit branches from the ancient oak tree providing an exhilarating counterpoint to the flowerlike blooms of

the fireworks and bonfire beneath and beside it. It hardly needs to be said how these complexities extend also into the notion of soundless- ness conveyed by the moon,

the comet and the oak tree alongside the noisy short-lived explosions of the fireworks.

Oak Tree, Bonfire and Fireworks is, at the same time, beyond any 'explanation', a painting about the state of being, a moment of ecstatic visionary

perception and self-realisation that places Inshaw in a direct line of descendance from Samuel Palmer in his Shoreham 'Valley of Vision' period. It comes as

something of a surprise therefore to find that Inshaw was brought up in Biggin Hill in Kent, less than ten miles west of Shoreham itself, and had, thanks to his mother,

already been introduced to Palmer's Darenth Valley on family picnics (as well as exploring the Kent countryside along the North Downs on long cycle rides). He

remembers that his mother seemed to know about Palmer, even pointing out the house where Palmer stayed, though how she knew this he cannot imagine. It was Inshaw's

first experience of an artist's life and work. In the context of his recent purely landscape paintings, it is worth considering more closely what this childhood

landscape was and may have come to represent for him imaginatively in later life. Irretrievably developed and built over in the mid-sixties, Biggin Hill was, in the early

1950s as Inshaw describes and remembers it, his valley of vision, a still largely countrified area where people from London built weekend shacks among the dense woods and

copses, a landscape, for him, full of mysterious incompleteness.

In describing his childhood, the stories Inshaw tells of growing up there are very much to do with the places and his experiences in them – of being out in the

countryside all day, of keeping rooks, birdwatching and of early sexual encounters in the woods on Bonfire Night – so that it soon becomes apparent that it is

through these new 'pure' landscapes that he is beginning to find a more profound and pictorially satisfying way back into these experiences than even his

highly successful paintings of the 1970s.

This new-found sense of self-revelation is apparent in Inshaw's other recent landscape compositions. Firework and Bonfire, West Bay [previous page] and

West Bay with Seagull and Horse, for example, mark, in personal terms, a moment of emotional upheaval, a last visit to the coast with a dying friend and the

virtually simultaneous start of a significant love affair. Yet to describe these works simply in terms of such obvious symbolism is also to ignore the delicate and

profoundly poetic balancing of complex elements that the artist brings to his work through the colour, mark and form of these compositions, our understanding that this is

no merely descriptive landscape always being, at the same time, quite immediate and intuitive. This is equally true of his other pure landscapes on Dorset and West Bay

themes, such as Dorset Landscape: Cerne Giant and Storm at West Bay – paintings of a resonant dramatic solitariness, quite literally

'charged' in some instances, and unmistakably autobiographical in character. They are, again, works which transcend symbolism, emerging as they do with

resounding power out of similar moments of being. Here, too, timelessness and silence play their part.

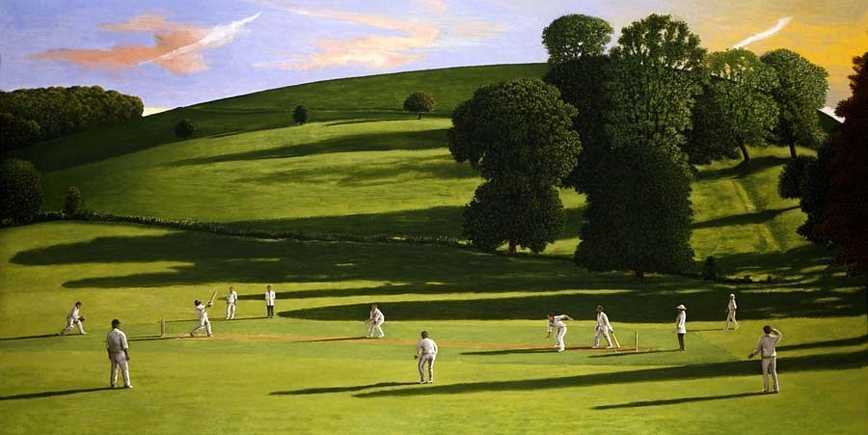

A further useful comparison of this distinct deepening of mood is provided by Inshaw's reworking of one of his best-known paintings from the 1970s, The Cricket

Game, a work of undeniably translucent and elegiac beauty set in a Dorset landscape. The new painting, The Cricket Game III, is infused with an altogether

different mood, richer and more sombre timbres of feeling, the almost ghostlike figures fading into an even greater insubstantiality within the sonorous chords of evening

light and towering trees. To use a musical metaphor, one moves here from a youthful Schumann piano sonata to the flickering lights and shades of a late Mozart piano

concerto.

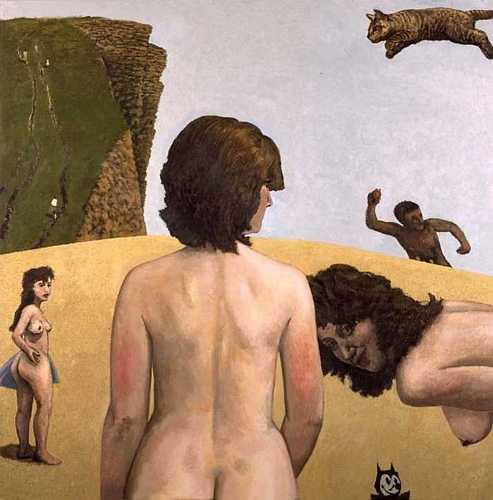

Interestingly it is the figure subjects, and particularly the West Bay paintings, which now convey the lighter and more fanciful side of Inshaw's imaginative personality, works like West Bay with Helicopter (Sunburnt Shoulders), West Bay with Leaping Cat and Felix, and West Bay with Pregnant Woman. Here the leaping cats, hovering helicopters, patient dogs, provocative fairies, pregnant women and Felixes (a favourite cartoon subject and here mischievously representing the artist himself admiring the female forms around him) assume an altogether more playful character, albeit tempered by the almost surrealistically disorienting juxtapositions of both landscape forms and the figures, human and animal, within it. As a consequence, silence and timelessness play their characteristic role here too, in creating images of quite particular, almost ironic memorability – this is not quite the seaside of fond and familiar memory. As the extended dates on most of these works suggest, they are paintings which have taken slightly longer to find their final form, an outcome perhaps of the focus on purely landscape themes in recent years and of the need to establish a new and distinctive 'voice' for his figure themes.

That Inshaw has unquestionably succeeded is confirmed by the fact that his figure paintings gave him the confidence to tackle by far the largest single painting of his career, The Corbin Family, a commissioned group portrait of the distinguished restauranteur Chris Corbin and his family (close friends over many years) which, at 6' x 12', must be one of the largest conversation-piece subjects produced in this country over the last half a century. Certainly it must rank as one of the most strikingly ambitious and successful, the subtlety of family relationships and personalities wittily and touchingly brought out by the positioning of the much valued au pair to balance the composition also suggesting the presence of a guardian angel. At the same time the landscape of Alsace, where Francine Corbin grew up, plays a defining role in the richness and relaxed intimacy of atmosphere that Inshaw manages to establish on such a large canvas, while the quietly circling barn owl and the lugubrious dog (a direct descendent of the one sitting in the cart in Douanier Rousseau's painting Old Junier's Cart) attest to his lifelong compassion for birds and animals.

In such a discussion of composition and subject matter, the huge importance of the new style and technique Inshaw has quietly developed over the last two decades must not be overlooked. The paintings of the 1970s that first made his reputation depended for their effect, to a very considerable degree, on a meticulous and incredibly painstaking sequence of tiny brush strokes. Almost pointillist in scale, the sheer time they took to paint was an intrinsic part of the rapt, intense atmosphere they so distinctly convey, but by the early 1980s this way of painting had become a kind of stylistic prison, one that did not allow for any very wide variation of mood or subject.

Starting with a series of smaller sea, garden and landscape paintings, Inshaw began to experiment with the much broader kind of brush strokes he had used as a student at Beckenham Art School, with hog's-hair bristles replacing the fine sable brushes used on works like The Badminton Game. The successful development of this technique for much larger-scale compositions is, in a sense, the story of his more recent work, paintings of almost hallucinatory intensity such as Cat and Bonfire, Pyrotechnics and Goldfinches unthinkable without it. This final painting stands very well for many of the themes and strands in Inshaw's art – the birds themselves fragile and joyous symbols of the various relationships with the people and places in his life, the frozen stillness and quietness of their flight placing them outside time and, imaginatively, inside our heads; the immanent mysteries and fantasies of his childhood landscapes in Kent resolved and enfolded in an epiphany of quietude and wonderment.